This is the first entry in a series on Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw. [Hold on! Keep reading! Don’t leave!] For context on why I’m doing the series, see here. For context on how I initially thought I would do the series, see the top of here. But — I am revising that approach! This is a fairly long essay, and I’m drafting another one that will be fairly long as well. They are both on the opening section of the story, which for convenience’s sake I will call “the prologue.” As I’ve said before, I don’t think you have to know the story for the posts to make sense, though obviously I’d encourage you to read it if you haven’t. (And also, no, there are no spoilers — c’mon now.) Anyway, instead of blogging my way through the story bit by bit, I’m going to use these two longer pieces as a sort of introduction to The Turn of the Screw — specifically, as a preface to the prologue. I’m also aware that we’re already well into October, and I can’t promise that the second part of the series will definitely be published by Halloween. As you will see, though, spooky season is not at all curtailed by October 31st. Also I make the rules here.

Last but not least, in a happy accident, this month marks the story’s 125th anniversary.

“I have visited some literatures of the East and West; I have compiled an encyclopedic anthology of fantastic literature; I have translated Kafka, Melville, and Bloy; I know of no stranger work than that of Henry James.”

— Jorge Luis Borges

The first thing to note about The Turn of the Screw is that it’s a Christmas story. Or rather, it’s a story told over the Christmas season. As far as I can tell, this detail seems to have gone relatively overlooked as generations of readers, from wonky academics to lounge chair Freudians to high school English teachers, have tried to piece together Henry James’s obscure, probably unsolvable puzzle. Could Christmas be the missing clue? The final variable to yield a unified theory?

No, but if there’s anything we can say for certain about Henry James, it’s that he was meticulous — or scrupulous, to use a word he seemed to like. In his celebrated essay “The Art of Fiction,” James argued that the ideal writer should “be one on whom nothing is lost.” He may have been describing himself.

So I don’t think it’s an accident that Christmas appears in the first line of the story. In fact it’s one of the few clear details in an otherwise confusing sentence:

The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless, but except the obvious remark that it was gruesome, as, on Christmas Eve in an old house, a strange tale should essentially be, I remember no comment uttered till somebody happened to say that it was the only case he had met in which such a visitation had fallen on a child.

What to make of that language? It features all the trademarks of a Henry James line: dense, disorienting, and to be blunt, pretty odd. The story had held us, round the fire, sufficiently breathless.... Even if we grant that, to our ears, a nineteenth century writer will inevitably sound stilted and overstuffed, James stands out: ordinary words are used in unusual ways; simple declarative statements are rare; complex verbal mazes proliferate across the page, as if to slow us down by design. Also there are commas, lots of commas.1 Still James was both a product of his time and one of its principle critics; an insider by birth, but an outsider by disposition. He considered his writing to be explicitly anti-Victorian, a rejection of the kind of bloated, never-ending nineteenth century novels he called “loose baggy monsters.” He was too old for the Bloomsbury Group, and passed away before the emergence of Eliot, Pound, and Joyce. But for his rigorous style, mythic sensibility, and subtle psychology, James was an early modernist. Or as a professor of mine once put it, “He got there first.”

To return to the question at hand, though: why Christmas? I think for two main reasons. The first I’ll address in this post, and the second in a follow-up.

The first is simply convention. Christmas is often associated with the supernatural. Not just in the singular event of the Incarnation, but in a more general (and quasi-pagan) sense. If ordinary time is plain and humdrum, festival time is strange and charged. Up is down and down is up, and spirits walk among us.2

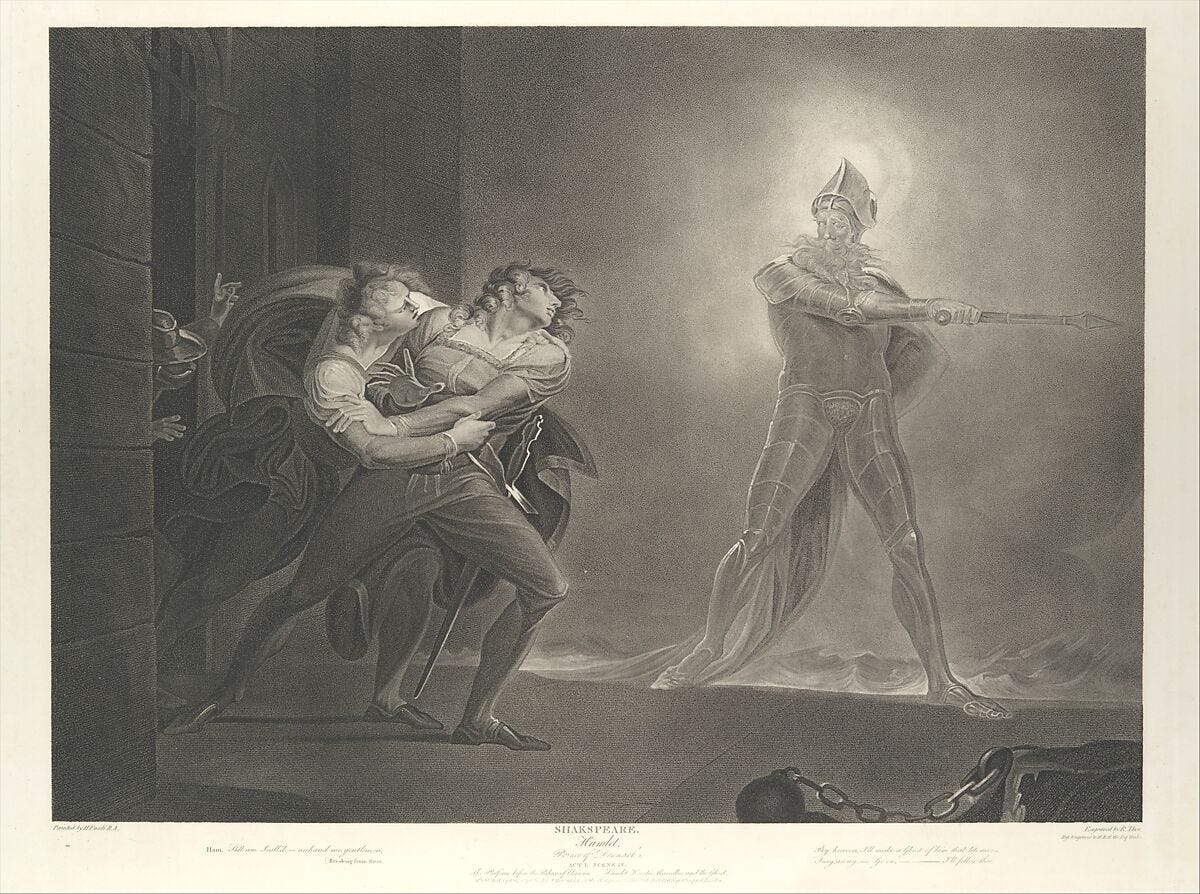

Hamlet, a play which hinges on a ghost and whether that ghost is to be trusted, seems to begin during Advent. Sir Gawain and the Green Knight, written in the late 14th century by an unknown poet, is more involved with faeries than phantasms, but the action starts on Christmas Day.

The Victorians loved telling ghost stories around Christmas, and Christmas Eve, in particular. Dickens’s A Christmas Carol remains the most famous example, but there are others. Take the medieval scholar, antiquarian, and Cambridge don, M. R. James — full name, Montague Rhodes James (contemporary of Henry, but no relation). Monty, as his friends called him, moonlit as one of the period’s most popular ghost story writers and still holds his claim as one of the genre’s very best. (If you’re into the kinds of stories in which erudite, tweed-wearing professors go on vacations to the Kentish coast only to be haunted by mysterious occult objects, Monty is your guy.)

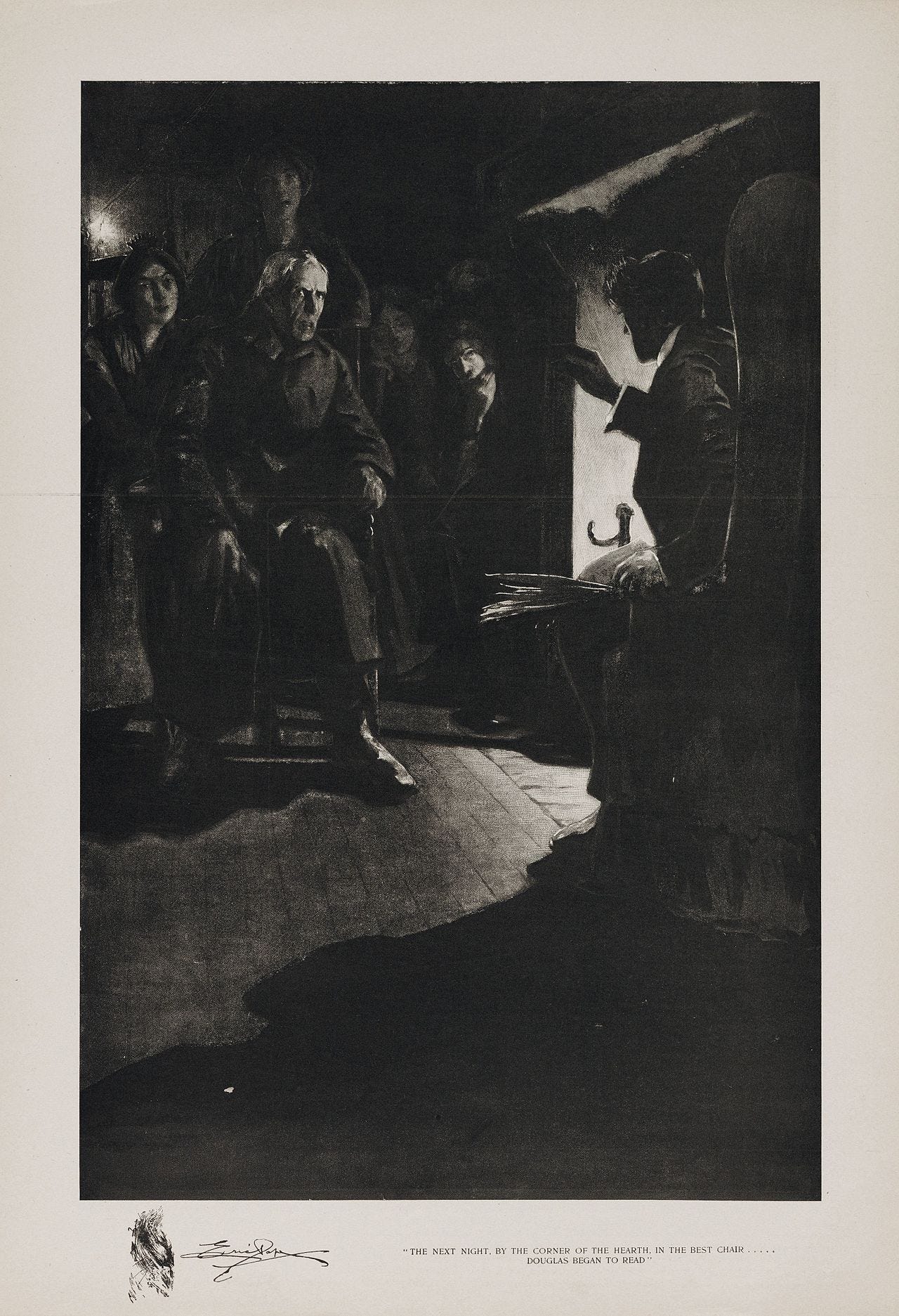

Every Christmas Eve, following the traditional Lessons and Carols service at King’s College Chapel, Monty would read the latest draft of one of his stories to a rapt crowd. Darryl Jones imagines what those meetings must have been like:

To close the evening, a select few, a very few — friends, colleagues, former students, retire to the Provost’s rooms, participants in altogether more sinister Christmas ritual. . . . Candles are lit, the Provost disappears into his bedroom; the friends talk, and drink their brandies or port, a little nervously. Perhaps someone plays a few bars on the piano, but always hesitatingly, and never for long. At last, the Provost returns, clutching a manuscript covered in a spidery, illegible handwriting that might almost be a private cipher, the ink still wet upon the final pages, and blows out all the candles but one. It is gone eleven, nearer midnight, when the provost begins to read, his clear, confident voice cutting through the dim, flickering light of candle and fire: ‘By what means the papers out of which I have a connected story came into my hands is the last point which the reader will learn from these pages . . .’

In its evocation of a hushed, fireside setting and a mysteriously sourced manuscript, the scene mirrors the opening of The Turn of the Screw. More to the point though, it illustrates something fundamental about the act of storytelling — that is, the sum is always greater than the parts. What counts is not just the physical environment, but the sensory experience; not just the author, but perhaps more importantly, the audience. After all, a story can only be told if an audience is present.

The Victorians understood this better than most. Henry James may have understood it better than anyone.

But at the time many people weren’t content with merely evoking the dead. They wanted to summon them. In the United States alone, at the close of the nineteenth century between four and eleven million people identified as Spiritualists. Among the movement’s leading lights included physicists and chemists Marie and Pierre Curie; Arthur Conan Doyle, who put a pause on writing Sherlock Holmes stories to write twelve books on the subject; and perhaps most famously, Mary Todd Lincoln, who hosted as many as eight seances in the Red Room of the White House, some of which the President attended, in an attempt to communicate with her deceased children.3

Today we might look back in wonder. How did so many people — including highly intelligent people — fall for something so obviously bunk? A few cultural currents are worth considering.

First was the growing desire to bring back, directly or indirectly, a more “enchanted” form of Christianity which the Reformation, and more recently Deism, had either tamped down or snuffed out. We can loosely tie this idea to specific movements like Romanticism, as well as broader trends like revivalism and syncretism. However you want draw up the taxonomy, it would’ve included wildly heterogenous subsets, each with their own particular vision of what enchantment entailed, from the incense and cassocks of a Catholic Mass to the snake handling and tongue-speaking of a Pentecostal tent revival. (Ergo I’m not sure how helpful the category is.)

Next, and closely related, would be what I’ll call the primitivist movement. This group would’ve included people who wanted to go back even further, who had turned away from the religion they’d grown up in, but still felt the pull of belief and were in search of alternatives. At the time, that often meant pre-Christian religions imported from the near and far East that offered a two-for-one: the feeling of a new and exotic experience, the fact of an old and credible practice.

But these are sweeping generalizations, and not the kind James and those he admired would’ve cared much about. If the trend of nineteenth-century history and philosophy was toward the systematic and abstract, literature — even the kind James ostensibly disavowed — tended toward the individual, and in particular, the individual’s complex, contingent, and unique relationship with society. Who can say why a certain belief might emerge or recede? Some believers might’ve been natural zealots, others might’ve been natural pushovers. Some were probably just bored.

Still, while Spiritualism may have been a fad for a few, the majority of people must have been sincere. In fact I imagine that for a lot of people, Spiritualism wouldn’t have felt like a choice so much as a necessity. A final, desperate leap, or a hopeless, forlorn plea. After all, nobody wakes up and decides that today they’re going to communicate with the dead without just cause.

Henry James was not a Spiritualist, but his brother was. Besides his renowned accomplishments as a psychologist and pragmatist philosopher, William James also helped found the Society for Psychical Research.

The Jameses had been one of America’s most prominent families. The brothers’ grandfather had come to New York from Ireland and died the second wealthiest man in the state, behind only John Jacob Astor. Their father, Henry Sr., attended Princeton Theological Seminary, wrote a book on the Swedish mystic Emanuel Swedenborg, and was friends with Emerson and Thoreau.

But they were not a happy bunch. From 1855-60, Henry Sr. moved his family back and forth between Newport, London, Geneva, and Paris, enrolling and withdrawing his children from dozens of schools. Mental illness plagued the family. Alice James, the younger sister of the family and a gifted writer in her own right, suffered neurasthenia and was bedridden most of her life. William and his father both experienced bizarre hallucinatory episodes, or what Henry Sr. called “vastations.”

One night, after putting his infant sons to sleep, Henry Sr. was staring idly into the fire when he was seized by “a perfectly insane and abject terror” of “some damned shape squatting invisible to me,” emanating death. The shock took two years to subside.

William suffered a similar life-changing episode when he was twenty-eight, soon after the death of his cousin Minnie, whom William had been in love with. Late one night, tired and gloomy, he walked into his dressing room.

Suddenly there fell upon me without any warning, just as if it came out of darkness, a horrible fear of existence. Simultaneously there arose in my mind the image of an epileptic patient whom I had seen in the asylum, a black-haired youth with greenish skin, entirely idiotic, who used to sit all day on the benches, or rather shelves, against the wall, with his knees drawn up against his chin, and the coarse gray undershirt, which was his only garment, drawn over them, inclosing his entire figure. He sat there like a sort of sculptured Egyptian cat or Peruvian mummy, moving nothing but his black eyes and looking absolutely non-human.

“That shape am I,” William concluded.

The personal blows would continue. In 1882, the year he helped found the Society, both his parents died. Another James brother, Wilky, died the following year. Finally, after the death of his one-year-old son in 1885, William reached out to the medium Leonora Piper. He was desperate, and by some inexplicable, “supernormal” power, Leonora answered his desperation. In a deep trance, Leonora murmured the name of his son, and William — polymath, depressive, “believer without a creed” — felt the flicker of belief.45

What did Henry believe? He occasionally attended meetings of the Society for Psychical Research with his older brother, and was familiar enough that some critics have suggested that The Turn of the Screw is partly based on published case studies. But in a letter written in November 1863, he poked fun at a lecture recently given by a medium in New York.

... She holds forth in a kind of underground lecture room in Astor Place. The assemblage, its subterraneous nature, the dim lights, the hard-working, thoughtful physiognomies of everyone present quite realised my idea of the meetings of the early Christians in the Catacombs, although the only proscription under which the … disciples labour is the necessity of paying 10 cents at the door.… Well, the long and short of it is, that the whole thing was a string of such arrant platitudes, that after about an hour of it, when there seemed to be no signs of a let-up we turned and fled.

It’s the sort of thing his brother would’ve hated. William wanted proofs; mostly he got frauds. Henry, on the other hand, might’ve appreciated the performance more than he let on. At least he might’ve picked up a lesson in craft.

The fact is, Henry James wrote many ghost stories. And he wrote ghost stories for the same reason that he ventured into the catacombs of Astor Place to hear a seance; the same reason that, twenty-five years later, on Halloween Night, 1890, he presented a paper of his brother’s, titled “Observations of Certain Phenomena of Trance,” to the Society for Psychical Research — because ghost stories are entertaining.

So in keeping with the spirit of the genre, if we haven’t already, let’s suspend our disbelief while making what I think are some reasonable speculations. If your brother is a leading parapsychologist, and you’ve personally participated in Spiritualist activities, you probably have an advanced knowledge of the subject. At the same time, if your brother is also a world-famous psychologist, and your family has a history of mental illness and hallucinatory episodes, you’re very familiar with the ways in which the mind shapes, distorts, and even creates reality. Above all, in both cases, psychology and parapsychology, you have the advantage of insider knowledge with outsider perspective. Over time you learn what evidence to dismiss and what’s worth paying attention to, what makes one case dull and another gripping. You learn the tricks of the trade, in other words — what makes for a good ghost story and a bad one.

Shortly after Christmas, on January 10, 1895, Henry James heard a particularly good one. Told to him by the Archbishop of Canterbury, a personal friend, the details were murky and second-hand, passed on by “a lady who had no art of relation, and no clearness.”6 But James made note of the essence in his journal: young children left to the care of servants in an old country house; the servants corrupting the children and dying under mysterious circumstances; the servants returning to haunt the children and trying “to get hold of them.” Again he emphasized, “it is all obscure and imperfect, the picture, the story, but there is a suggestion of strangely gruesome effect in it.”

The obscurity was the point. If the story had been cut-and-dry — the kind of story his brother longed for — there wouldn’t have been much for James to do. Case closed. Instead there was no solution at all, and less of a plot than an eerie, troubling palimpsest. But that was all James needed. He knew what the story was, now he just need a way to tell it.

Well, why not reuse the conventions that always worked? The gothic setting, the Christmas background, the familiar, piquant notes that would hold his audience “subject to a common thrill.” Still James wouldn’t just imitate supernatural tropes like some second-rate writer or charlatan of the occult. He was a modernist. If he reused some conventions, he would also upend them. The Turn of the Screw both is and isn’t a gothic tale. Christmas is mentioned once, then forgotten.

James’s most crucial decision was one he made almost immediately. The final note of his journal entry reads: “The story to be told — tolerably obviously — by an outside spectator, observer.” In other words, someone not unlike James himself.

… Preface to be continued in the next post.

We’re a long way from Hemingway, and a very long way from McCarthy, who infamously accused James and Proust of not “deal[ing] with issues of life and death,” which is a statement so unfounded that you’re forced to assume he’d either never read their work, or simply was fucking with interviewer. “I don't understand them . . . to me, that’s not literature. A lot of writers who are considered good I consider strange.” Vintage stuff.

Specifically I’m thinking of the difference between chronological time versus kairotic time, and borrowing from Charles Taylor’s account of “buffered” versus “porous” experiences of the world. Another helpful term here, from apocalyptic theology, is “inbreaking.” Good word.

Incidentally, the Lincoln White House may not have been the last administration to engage a medium. Circumstantial evidence, as well as at least one first-hand testimony, suggest that Edgar Cayce, “The Sleeping Prophet,” gave readings to Woodrow Wilson after the president’s stroke and failed campaign to ratify the League of Nations in 1920. For more, see Sidney Kirkpatrick’s American Prophet.

For the quote and biographical details that informed this section, credit to Emily Harnett’s essay in Lapham’s Quarterly, “William James and the Spiritualist’s Phone.” See also Robert D. Richardson’s William James: In the Maelstrom of American Modernism.

I had no intention of mentioning Cormac McCarthy anywhere in this essay, but here he is in the footnotes again. To wit, there is a remarkable symmetry between parts of the James family’s biography and the family at the center of McCarthy’s final pair of novels, The Passenger and Stella Maris, specifically between siblings William and Alice James and the fictional Bobby and Alice Western. Besides their names, similarities include exceptional intelligence (especially within the arts and sciences), chronic depression, hallucinatory episodes with no definite diagnosis, religious and philosophical skepticism, and most importantly, a doomed incestuous desire for one another.

As it happens, the Archbishop had founded the University of Cambridge “Ghost Club,” a forerunner to the Society of Psychical Research.