“Oppenheimer” and The Biopic Trap

Plus an October reading club and the greatest work of art ever

More spare and desultory thoughts this week, because it’s August and it’s very hot. Everywhere seems very hot. Here among the relatively lucky, we happy few who only endure damp brows and soiled clothes in midmorning and the feverish drone of monstrous insects, a late summer listlessness descends.

And why should I resist?

October Reading Club

For anyone interested in reading along, I’ll be blogging my way through The Turn of the Screw this October.

The Turn of the Screw is a short novella, a little over a hundred pages depending on the edition, and yet is as dense and convoluted as anything in the English language. I’ve heard it called the most claustrophobic story ever written; it’s undoubtedly one of the best ghost stories ever written; a lot of people probably find it completely tedious.

As far as I can remember, my first encounter with this “shameless potboiler,” as James called it, would’ve been in 2009, the fall of my junior year, in a Modern American Fiction class. Around October 2017 I read the story again to get in the Halloween spirit (which is weird, because I’ve never been a Halloween person). Since then I’ve re-read it every October, until last year when I took a hiatus.

Anyway, I’m not sure that you’ll absolutely have to read the book in order to understand the posts, but it’ll help. Maybe you’ll even have fun, who knows? I’ll be going through it in sections, so I’m guessing we’ll cover 30-40 pages a week. There are plenty of dirt cheap copies available, and I’m giving you a six-week head start so you don’t have to order from Amazon. I’ll post more reminders in the coming weeks.

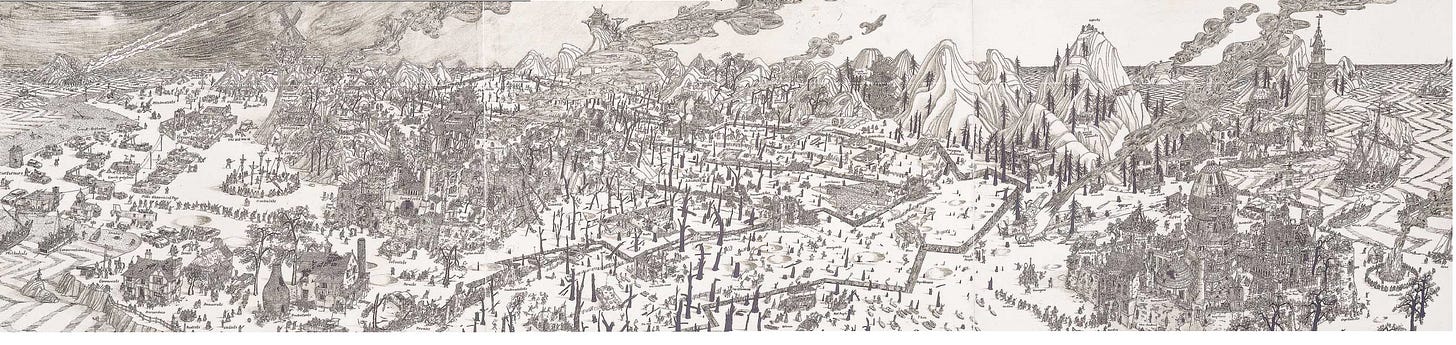

Grayson Perry’s Print for a Politician

With all due respect to other candidates, Grayson Perry’s Print for a Politician is the greatest work of art ever. Open it up as a full page.

Oppenheimer and Avoiding The Biopic Trap

Oppenheimer is a good movie that stumbles in ways we’ve come to expect from a Christopher Nolan film: a few too many timelines, more characters than anyone can reasonably be expected to keep up with, and strange, distracting stunt casts.

(A real-time breakdown of my viewing experience: Why is Rami Malek in this movie? . . . Who is Rami Malek in this movie? . . .

. . . Jesus Christ, that’s Rami Malek.)

But for all its flaws, the movie successfully navigates its biggest obstacle, which has undone so many of its predecessors: the biopic trap.

The biopic trap takes place when a film featuring real-world characters and events, either from history or the present day, prioritizes accuracy, authenticity, and comprehensiveness over structure, story, and coherence. In short, the biopic trap is what happens when biography overwhelms picture. It’s why this particular genre — if we can call the biopic a genre — tends to elicit so many eye rolls. Narrative caution is thrown to the wind and the result is — as the aforementioned Henry James described 19th century novels — a “loose baggy monster.”

If a typical biopic adheres to any narrative structure, it’s either the rise-and-fall formula — predictable, treacly — or even worse, the and-then plot, in which the only mechanism tying the story together is an endless string of plot twists: this crazy thing happened, and then this crazy thing happened, and then this truly insane thing happened, etc. Eventually so many twists take place that the plot either gets tangled up or simply unravels. (Comedy and action films use a similar heightening effect all the time, but with a sense of irony that’s largely absent in biopics.)

None of this is to say that the genre is inherently bad. Just looking at movies released in the past few decades, The Wolf of Wall Street, Moneyball, and The Social Network are all technically biopics. Hell, Lawrence of Arabia is a biopic. But the bad ones nearly always mistake celebrity for story. In other words, they assume that a character’s sheer persona — mere existence — is enough to warrant depiction on screen. And the more depiction, the better. Give us his awkward adolescence, his grueling coming of age, his triumphant annus mirabilis. (Let’s be real, it’s usually his.) Give us his feats and glories, his decline and fall. But don’t stop. Keep going. Does he rise again? Give us that, too. Give us what, you presume, we came for: the true, definitive, behind-the-scenes tell-all saga. Give us everything.

The reason this approach fails is because even the most interesting people in human history lead lives that are marred by trivia and boredom. Not everything about the life of Johnny Cash or J. Edgar Hoover — or even, according to the Gospels, Jesus Christ — is worth mentioning. A bad biopic doesn’t make such distinctions; it doesn’t make any. It just wants to claim authority based on thoroughness.

The alternative is a movie that knows where to cut corners. What can be omitted or altered in a way that not only maintains the integrity of the story, but actually throws new light on it? At a full three hours of runtime, the last of which feels both drawn out and rushed, Oppenheimer is not exactly compact. The edges start to blur, reality gets a little soupy. But if a movie about scientists debating quantum physics in the desert happens to play with our sense of being and time, so be it.

“Tell all the truth but tell it slant,” Emily Dickinson wrote. You don’t have to tell Nolan twice.