What I've Been Up To

Tonie reconnaissance, HVAC armageddon, Walker Percy, et al.

...See? I wasn’t gone that long. I doubt any of you missed me, and I damn near know none of you spent the last six weeks evangelizing The Happy Few.

A few things I’ve been up to...

Not twelve hours into 2024, my two-year-old dropped her new Paw Patrol Tonie inside the cavity of a yet-to-be-assembled push car. (A Tonie is a toy figurine that plays audio when placed on top of a paired Tonie sound box. In other words, it’s a fancy radio for screentime-conscious-but-ultimately-resigned parents.) At first I was like, no big deal, I’ll just shake the car until the Tonie falls out, the same way I’d rescue a guitar pick that falls into an acoustic guitar. But surprise! It wasn’t that simple.1 The car’s anatomy turned out to be strangely complex, a multidimensional maze of hidden tunnels and passageways that made it seemingly impossible to dislodge our victim. No matter how much I shook the car over my shoulders, all the while looking out for the shadow of the Tonie through the vehicle’s red plastic shell, the figurine was no closer to working its way down into the opening. The situation was becoming dire, and with every minute that passed the Tonie’s survival seemed increasingly in doubt.

But wait! Maybe I was doing this all wrong. If someone falls into a crevasse, you don’t hope for an upside-down earthquake. You throw down some rope. In a moment of inspiration, I remembered that Tonies are magnetic. Maybe I could draw it out. But with what? I rummaged through our kitchen cabinets in search of a tool that might work: knives, tongs, a honing rod — nothing flexible or long enough to navigate the car’s byzantine intestines. And then, aha! My dog’s pinch collar. I unhooked the ends and dropped the chain into the opening. After about ten minutes of trial and error, our victim emerged from the vehicle, chastened but unharmed.

A week later, I welcomed a new kid.

A few days after that, and not thirty minutes into welcoming our new kid home, I realized that the distinct chill in our living room was not going away. The heat was out, and the forecast that week called for consecutive lows in the teens.

This is not a personal finance blog, but a word of advice: never, and I mean never, have to replace your heating and air system. Never.

I read and considered Steven Hyden’s ranking of Radiohead and Radiohead-adjacent albums.

I listened to The Smile’s recently released Wall of Eyes, i.e., one of those Radiohead-adjacent albums. Hyden heard a kind of OK Computer b-side. Personally, both of The Smile’s albums remind me of Amnesiac, itself a kind of b-side to Kid A. In any event, I’m not complaining.

I read John Jeremiah Sullivan’s introduction to a new edition of Guy Davenport’s The Geography of the Imagination, one of the wildest, weirdest, and most intimidatingly intelligent books I’ve ever read.

Incidentally, I first heard about Davenport in a Paris Review blog post by Sullivan twelve years ago. Throughout my twenties, I returned to Davenport again and again, especially The Hunter Graachus. But Geography remains a touchstone, the kind of book that didn’t so much change how I read as it made me second-guess if I knew how to read in the first place.

Born in Anderson, South Carolina, Davenport earned his PhD in English Literature from Oxford, the first person in the school’s history to write a dissertation on Joyce. He’d read everything and could write about anything. Not just poets and novelists, but cave art and cubism, Shaker furniture and the labyrinth of Crete. The famous opening line of Geography reads:

The difference between the Parthenon and the World Trade Center, between a French glass of wine and a German beer mug, between Bach and John Philip Sousa, between Sophocles and Shakespeare, between a bicycle and a horse, though explicable by historical moment, necessity, and destiny, is before all a difference of imagination.

This essay, which gives the book its title, is ostensibly about Edgar Allen Poe but goes on to discuss, among other things, Victorian interior design, Oswald Spengler, Joyce (always Joyce), Ovid’s Metamorphoses, and the intricate iconography of Grant Wood’s American Gothic, including a brief history of button holes. The only other writer I know who can pull off this sort of act, balancing one’s towering intellect with the confidence and grace of a seasoned brasserie waiter, is Roberto Calasso, the Italian polymath. Both were enamored with myth; both exuded an artless, unbothered bohemianism. But where Calasso could be ponderous, Davenport harbored a wry sense of humor. As the onetime student of a certain “mumbling and pedantic” lecturer in Anglo-Saxon, he was shocked to discover that this same person, Professor Tolkien, had gone on to publish The Lord of the Rings. Years later while teaching at the University of Kentucky, Davenport happened to meet an old college classmate of Tolkien’s. Originally from the small town of Shelbyville, the man had heard about his friend Ronald’s success but hadn’t read a word concerning Middle Earth. “Imagine that,” he told Davenport.

You know, he used to have the most extraordinary interest in the people here in Kentucky. He could never get enough of my tales of Kentucky folk. He used to make me repeat names like Barefoot and Boffin and Baggins and good country names like that.

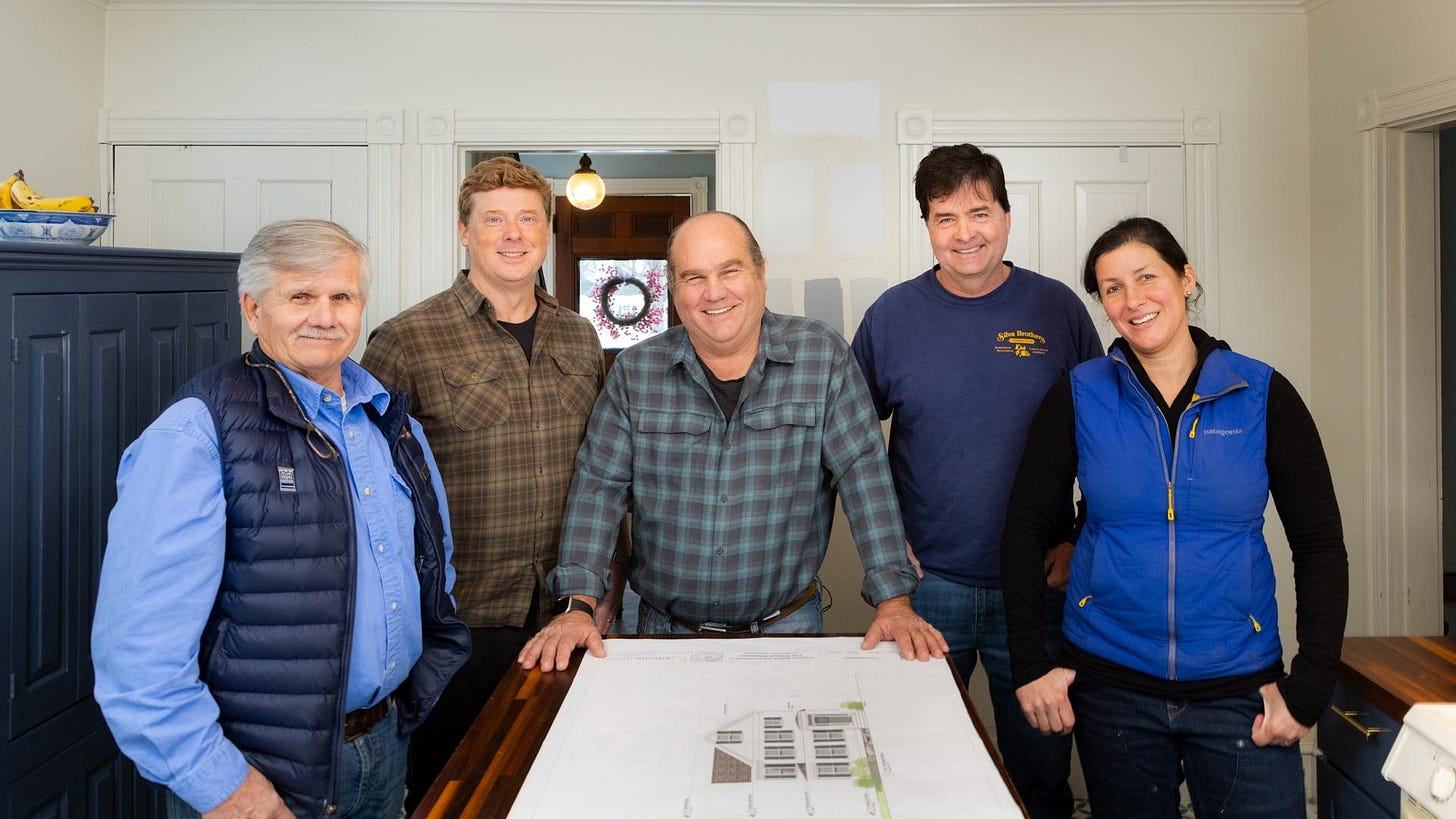

I watched a lot of This Old House, several seasons of which are available for free on their app. The show has been on the air since 1979 for good reason. But I have to admit, especially following my HVAC debacle, I’m dying to know what some of these renovations must cost. (Apparently budget was discussed more in the early days.) I mean, I too would love to punch up a two-hundred-year-old New England manse with ultramodern amenities, net-zero emissions, and a few choice additions — all while honoring and preserving the historic character of the house, of course — but methinks this adds up to a sizable bill, no?!?

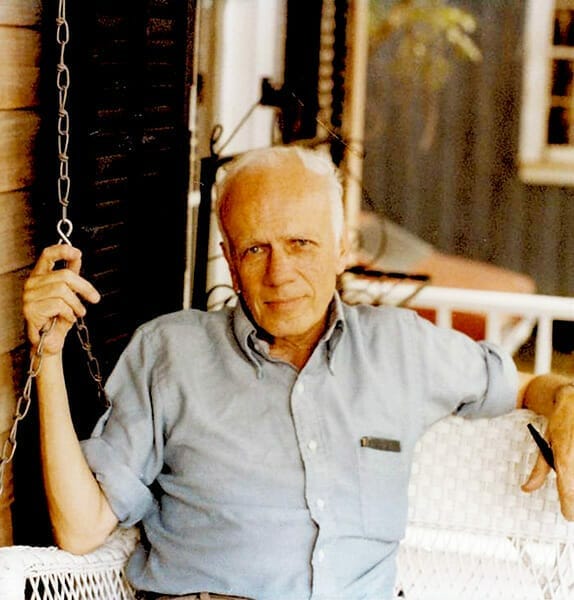

I picked up a few books and finished none, though I read several essays from Walker Percy’s Signposts in a Strange Land.

Percy has always struck me as a strange guy. As a fiction writer, he is easy to admire but hard to love. Same goes with his essays. His penchant for philosophizing on everything from the meaning of language to the meaning of bourbon can be a little grating. His central preoccupation is malaise; or to paraphrase an analogy he liked to use, that dull, insidious dread which creeps in on a Wednesday afternoon around three o’clock.

He was a trained physician but abandoned medicine after contracting tuberculosis. A devout Catholic, he was obsessed with the Lutheran Kierkegaard. He descended from an old, strange, wealthy, and depressive Mississippi Delta family. He could be funny, dour, charming, and obscure, all at once. The role of the novelist, he once wrote, was “to give joy and to draw blood.” For his part, he was either among the last of the so-called Southern Renaissance writers or the first of whatever came after. He appreciated Faulkner but made a point to note that Faulkner was often full of shit. He praised Eudora Welty and Flannery O’Connor, both of whom were better writers than he was (which is no insult). He was a dabbler with a habit of poking his nose into highly contentious academic fields like semiotics and the philosophy of language. He was one of a handful of de facto literary spokespeople for anything related to the “state of the South” but eventually (and understandably) came to resent that role.

He lived in Covington, Louisiana, about a 45-minute drive from New Orleans on the north shore of Lake Pontchartrain, a place he described as “a pleasant nonplace” and “a backwater of a backwater.” Half-a-century’s worth of urban sprawl later, I can confirm that Covington basically remains a nonplace, though I’m not sure Percy would’ve found it as pleasant now. Even in 1980, he worried that it was “in serious danger of being written up in Southern Living.”

His rationale for this location made plenty of sense, though. Contrary to popular mythology, noteworthy places are rarely conducive to quality writing. Cost-of-living alone is a problem, not to mention the everyday diversions of city life. For Percy, New Orleans was a place where “one is apt to turn fey, potter about a studio, and write feuilletons and vignettes and catty romans à clefs.”

Today it seems like the pendulum has swung back in the opposite direction: remote mountainsides, windswept meadows, and solitary, rustic cabins are places where social media imagines writing happens. You sit down in a field of golden wheat and compose a passionate lover’s lament, or perhaps some free verse on the beautiful patch of flora that recently popped up in your backyard, which you have not yet identified but which later turns out to be a toxic invasive species. Of course both of these fantasies — cultured metropolis, pastoral wilderness — underscore a fundamental desire to be, or appear to be, interesting.

But writing isn’t interesting. Carpentry is interesting. Salvage diving is interesting. Selling life insurance, while perhaps not interesting, at least requires a formal license. You’ve got to work for it. You can even make money! Writing is dull, dangerously democratic, and basically non-remunerative. Sometimes it’s serious, even self-serious, but it’s not interesting. It’s barely even work.

Percy liked to tell a story. He was getting a haircut in Covington when the barber asked him what he did for a living. Percy responded that he wrote books. The barber said, “Yes, I know, but what do you really do?” Percy smiled and said, “Nothing.”

All for now. Have a good one, my dears.

And perhaps I should’ve known. As anyone who has seen Paw Patrol knows, the show exists in a kind of Agambenian state of permanent emergency.

Obsessed with all of this.