Note: In the event you aren’t interested in pseudo-theology — and really, why would you be? — feel free to skip this one. I’m late in getting out a post that was intended to be simple and for some reason isn’t. Anyway, instead of finishing that post, I’m cheating and republishing a lightly edited version of something I was asked to write for Lent on Luke 13:31-35, with added footnotes. The basic context is that a group of Pharisees have come to warn Jesus that Herod is planning to kill him. The commentary below is about his response.

This is a weird, funny passage — spicy, as the kids say. “Go and tell that fox” always catches me off guard. It turns out Jesus isn’t above the occasional insult.

But there’s more. In most English translations, the exact phrase is “that fox,” and I think the “that” increases the offense. “That fox” is both overfamiliar and dismissive. It implies that Herod while is particular, he isn’t unique.1 After all, the world is full of foxes — shifty and cunning agents, not to be trusted — and strictly speaking, “Herod” is a political title. Like every other Herod (including the Herod who already tried to kill Jesus) this Herod will be replaced by another.2 And like every other Herod, then and now, this Herod doesn’t understand what Jesus is up to.3

So, as if to avoid any confusion, Jesus lays it all out. “Listen,” he says — and I wonder if he took a deep breath here — “I am casting out demons and performing cures today and tomorrow, and on the third day I finish my work.”4

If the scene ended there, you could chalk it up as an especially heated rebuke that culminates in a judgment against Jerusalem.

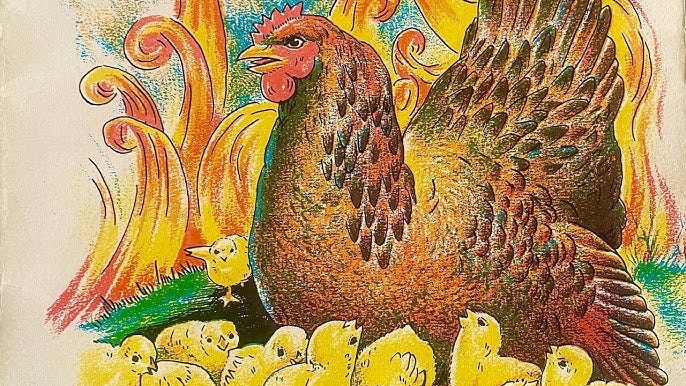

But Jesus goes on, renewing the metaphor. If a Herod is a fox, Jesus is a hen. Foxes are clever and cunning. Chickens are, from my understanding, neither.5 But Jesus doesn’t want to be a fox. He wants to gather his children under his wings, if only they would let him. On the surface, the image seems comforting, even sentimental, but according to N. T. Wright, what Jesus is actually describing is how a hen behaves to protect her chicks when a fire breaks out in a barn.

So like I said, this is a weird passage, which reveals Christ’s character and mission in a series of subtle and not-so-subtle ironies. The sense of righteous impatience reminds me of the scene in The Two Towers in which Gandalf scolds Grima Wormtongue, a cynical political opportunist not unlike Herod.

The wise speak only of what they know... Therefore be silent, and keep your forked tongue behind your teeth. I have not passed through fire and death to bandy words with a serving-man till the lightning falls.

Just then, thunder sounds in the distance.

Of course the same can be said of anyone, and the implication isn’t necessarily negative, cf.: “God shows no partiality,” otherwise translated as “God does not show favoritism,” or best of all, “God is no respecter of persons.” Un-uniqueness or in-distinction doesn’t concern this God.

The Herod of this story is Herod Antipas, who executed John the Baptist. About thirty years earlier, according to Matthew, Joseph and Mary fled to Egypt with the infant Jesus to escape the Herod the Great, Antipas’ father, then later returned to Nazareth instead of Bethlehem to avoid Herod Archelaus, one of Antipas’ brothers. There are six Herods in the New Testament, and they’re all bad news.

Again, as with the above footnote, the same can be said of Christ’s own disciples and many (most? all?) Christians throughout history. In Matthew 16:18, Jesus tells Peter that he will be “the rock” of his church. In Matthew 16:23, Jesus tells Peter, “Get thee behind me, Satan!”

I can imagine an underpaid teacher or overworked parent taking a similar tone.

See, for example, Werner Herzog’s legendary comments on chickens.