I was trying to finish a long, ambitious post before Christmas, but then I asked myself why? and couldn’t come up with any good reasons to rush delivery. So this will probably be the last post of the year and very well could be the last post for a while: I’ll be on paternity leave starting in early January. How will you get by without me? I honestly don’t know, but I trust you’ll figure it out.

I will be back, though. So as a final programming note...

Remember those emails you used to get in 2003 that were like “if you don’t forward this email to 12 people, your best friend’s war-hero grandfather will be indicted for treason this very afternoon!!!!”? Those were effective emails, and I would like to follow their lead.

Despite my reluctance to focus too much on readership stats, I do want more people to read my work. Any writer that says they don’t care about their audience is lying. (This is in part what the piece I’ve been working on is about.)

So, if you enjoy the newsletter, please consider sharing it with some like-minded soul. You never know: the life you save may be a patriot’s.

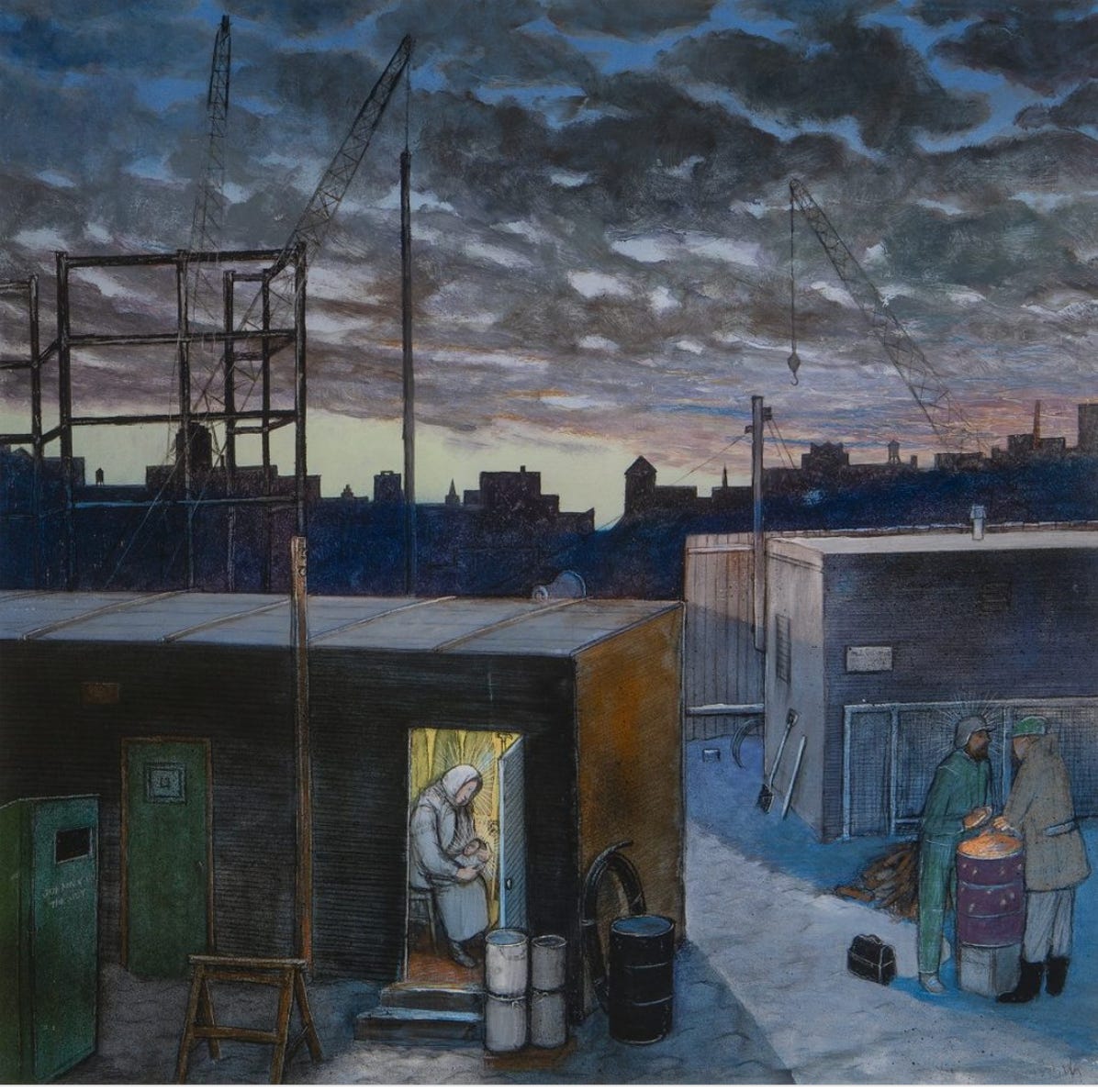

The Wicked Fairy at the Manger

My gift for the child:

No wife, kids, home;

No money sense. Unemployable.

Friends, yes. But the wrong sort —

The workshy, women, wogs,

Petty infringers of the law, persons

With notifiable diseases,

Poll tax collectors, tarts;

The bottom rung.

His end?

I think we’ll make it

Public, prolonged, painful.

Right, said the baby. That was roughly

What we had in mind.

— U. A. Fanthorpe

Fleming Rutledge likes to say that Advent begins in the dark. The light is coming, but we will have to wait for it. It’s a kind of (deliberately) awkward in-between season that we’d all just as soon skip — and in many ways do. But the odd thing about Advent is that anticipating its end is not unlike anticipating the end of the world. Advent is about the apocalypse; or if that’s too strong, Advent is concerned with the apocalypse. Whatever that means to you, surely it means something (?). Surely in all of history we have never been closer to the end than we are today (!). Christmas marks a birth, but not a treacly, sentimental one. A good birth, but not an easy one. The incarnation is a messy, muddy business, and one way or another, we’ve been dragged into it.

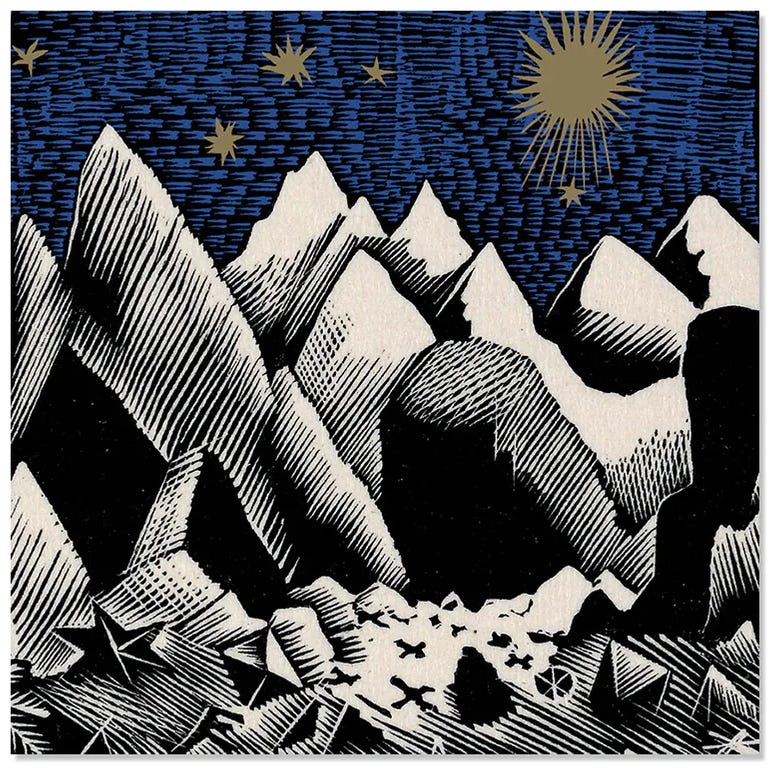

T. S. Eliot articulates this feeling in “Journey of the Magi,” his icy reimagining of the wise men’s journey to Bethlehem.1 It begins with lines borrowed from a 1662 Christmas Day sermon by Lancelot Andrewes (delivered at a service attended by King James).

‘A cold coming we had of it,

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.’

From there, the narrative turns into a dreamy picaresque: weird, inhospitable villages; tired camels; drunken camel drivers. The journeymen miss the pleasures of home:

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

And the silken girls bringing sherbet.

Though they reach their destination just in time, we get next-to-nothing about the actual nativity scene. Instead the hyper-educated astrologers seem to be at a loss for words.

[...] were we led all that way for

Birth or Death? There was a Birth, certainly,

We had evidence and no doubt. I had seen birth and death,

But had thought they were different; this Birth was

Hard and bitter agony for us, like Death, our death.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.

Something has ended, and something else has begun. But because this other thing is so new — and hard and strange — language fails to capture it.

Olivier Messiaen wrote several Christmas-themed pieces, including La Nativité du Seigneur and Vingt Regards sur l’enfant-Jésus, but in keeping with the apocalyptic tenor above, I think his Quatuor pour la fin du temps functions in the same vein. Written and premiered while Messiaen was in a Nazi POW camp, the Quartet is hard to describe, so I won’t try. If you don’t listen to the whole piece, at least listen to the fifth movement, which the New Yorker critic Adam Ross has called “excruciatingly beautiful.”

Last year, Hugh Morris published a fun article in the New York Times titled “‘Everyone Wants to Hear’ This One Chord in a Christmas Carol.”

In British choral circles, this moment is referred to simply as “The Chord.” It comes halfway through the final verse of the popular Christmas carol “O Come, All Ye Faithful” (or “Adeste Fideles”), in a mid-20th century arrangement by David Willcocks, an original editor of the widely used “Carols for Choirs” series and a former director of music at King’s College, Cambridge. Willcocks, following a rising figure full of anticipation, places an explosive, half-diminished seventh chord under the text “Word,” resolving it elaborately over the next few measures.

Maybe you know the chord in question, which seems to irrupt out of nowhere to produce a jarring, overwhelming effect, especially due to its location and relationship with the surrounding music. It has a rawness and a rareness. In another essay discussing The Chord from 2020, Aaron James writes:

There are special rituals that surround the playing of The Chord in most choirs: it is taken for granted that The Chord will be played each Christmas, but usually it’s only played once, at the midnight Mass on Christmas Eve, carefully avoiding any repetition that would spoil its effect. Every organist worth his salt knows never to play The Chord before the twenty-fourth of December; if “O Come” is requested at a Christmas concert or sing-along earlier in the month, the last verse should be played using the chaste, simpler harmonies of the hymnal.

Morris finds inspirations for The Chord in Bach’s “St. John Passion” as well as another arrangement of “O Come” by John Stainer in 1876. Meanwhile James notes that The Chord is actually a “close cousin of the languorous Tristan chord from Wagner’s Tristan und Isolde,” which anchors one of the most famous and tantalizing progressions in music history. In that case, we might even be able to trace The Chord back to around the turn of the 16th century, where its darker undertones emerge in the figure of Carlo Gesualdo, the singularly strange madrigalist who murdered his wife and her lover after discovering their affair.

As Werner Herzog explores in his quasi-documentary “Death For Five Voices,” Wagner was fascinated by Gesualdo’s work while composing Tristan und Isolde, in particular Gesualdo’s groundbreaking use of the chromatic scale. (Herzog’s full documentary doesn’t appear to be available for streaming anymore, but it’s worth checking out if you’re interested.)

All that is to say — The Chord’s history is as rich as its actual sound.

Finally, the fact it coincides with “Word of the Father,” alluding to the opening of the Gospel of John, carries a deep theological significance, as well. As a music director explains to Morris:

“To line it up with that chord not just reinforces the mystery of the text; it grabs you, makes you concentrate, and makes you confront it.”

Some notable books I read this year, in no order.

Nostromo and Typhoon and Other Stories, Joseph Conrad. I read a lot of Jospeh Conrad books this summer; not sure why. When he is good, he is really good. Conrad can be controversial, but I’m not sure how you can read a passage like this one from Nostromo, in which the enterprising Charles Gould outlines his philosophy of capitalist progress, and detect anything but a bitter, piercing irony.

“What is wanted here is law, good faith, order, security,” Charles said. “Anyone can declaim about these things, but I pin my faith to material interests. Only let the material interests once get a firm footing, and they are bound to impose the conditions on which alone they can continue to exist. That’s how your moneymaking is justified here in the face of lawlessness and disorder. It is justified because the security which it demands must be shared with an oppressed people. A better justice will come afterward. That’s your ray of hope.” His arm pressed her slight form closer to his side for a moment. [...]

She glanced up at him with admiration. He was competent; he had given a vast shape to the vagueness of her unselfish ambitions.

“Charley,” she said, “you are splendidly disobedient.”

Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, and Tomorrow, Gabrielle Zevin. Everyone liked this, so naturally I didn’t want to. I did. A little melodramatic? Sure. Sure! Nostromo is melodramatic, too.

Never mind, I remember why I read a lot of Joseph Conrad — David Grann’s The Wager, which I wrote about here. This was the year I realized that I harbor maritime fantasies.

Robert MacFarlane — anything. I read four MacFarlane books this year (well, three-and-a-half). If I had to choose favorites, I’d go with Landmarks or The Old Ways. MacFarlane’s passion for nature, language, and our relationship with the two is thrilling. Even when he is recounting a mundane walk around the neighborhood, he will reward you with words you’ve never heard, writers you’ve never read, and stories that most people have forgotten. A strong recommendation for anyone, but especially if you enjoy the work of Patrick Leigh Fermor, Nan Shepherd, Barry Lopez, Rebecca West, Robert Frost, W. H. Auden, the Lake Poets, or Paul Theroux, among others.

That’s all! A sincere thank-you for reading.

Again, if you’ve enjoyed The Happy Few, please consider passing it along. It’s the best way to reach the kind of readers I want to reach.

For now, good night and good luck.