More Thoughts on Certainty

Re: ordinary people, Descartes, and the self

Editor’s Note: The following is the first of two emails I sent to Cass Lowndes after he sent me his “prolegomena” on nerds. Knowing Cass, I knew he’d want to know how his piece was received. Rather than tell him it was, to date, the least popular post on The Happy Few per Substack’s analytics, I thought I’d offer a somewhat tangential response to the piece. Cass seems to have limited internet access, and as far as I can tell doesn’t know to access this newsletter, but agreed to let me copy my response here.

Cass,

I recently saw a quote from a professional philosopher who said that, given the discipline’s complexity, there’s no point in doing philosophy unless you’re extraordinarily good at it. I think that’s a fair argument, but on behalf of those who aren’t extraordinarily good at anything, I have to ask — what if it’s totally wrong? What if philosophy is only worth doing if you are extraordinarily bad at it? Not bad like, your actions are dangerous and have resulted in material damage. But bad like, your actions are futile and have resulted in nothing. The question is, who needs philosophy more: the experts or the rubes, the wise or the foolish?

Well, by nature or nurture, I find myself a member of the second variety — the proletariat of the incompetent — and maybe that’s for the best. Most of us will never achieve excellence as defined by the extraordinarily good. In that case, we can only tip our caps, wish our counterparts the best, and with the stealth of a skulk of fleet red foxes, high-tail it, never to look back, as if we were fleeing the clutches of the undead.

And maybe we are. Sure, a single extraordinary person can be compelling, if occasionally grating. But a host of extraordinary people is nearly always fatal: at any given moment, one can either die by violence or boredom.

As for the rest of us ordinary finite creatures, I think we should see our workaday badness as a gift: a chance to live beyond the scandal and mediocrity of excellence, attending not to grand and sweeping initiatives but to small, unseen labors — paltry, picayune things — without which everything else is vanity.

In short, consider the following my contribution to the school of bad philosophy.

Belated thanks for your note on nerds. I think you’re right, even if by your own definition it’s a little nerdy. I’ll take that as intentional.

I just read Lesslie Newbigin’s Proper Confidence, and I think he would agree with your skepticism of certainty. He ties the modern form of certainty back to Descartes and the “illusion” — his word — of total objectivity and truth deemed “indubitable” — Descartes’ word. But Newbigin argues that certainty’s claim on truth is limited and reductive — or more precisely, certainty is limited because it’s reductive. To be certain of something is to exclude any possible doubt. Therefore to be certain of something is to have reached a definitive conclusion. But as long as we live within the continuum of capital-H History, are definitive conclusions possible? To say yes would be the equivalent of claiming to know the full plot and purpose of a story before we’ve reached the end.

Therefore I would argue that while certainty claims to have achieved a definitive answer (often through human-centered heroic means like ingenuity, discipline, strength, etc.), in fact it’s an unwitting attempt at a shortcut. In a sense, then, certainty is cheap.

What? How? Let’s go back to Descartes. In a letter dated January 19, 1642, Descartes wrote:

I am certain that I can have no knowledge of what is outside me except by means of the ideas I have within me.

It’s a deceptively tidy sentence with vast implications — e.g., The Enlightenment. We’ll use it as a high-level summary of Descartes’ philosophical method.

First, note that he actually does begin with doubt. In order to be certain of anything, we must attempt to disengage from everything. From there, once we’ve set side all possible objects of doubt, we’ll see that the only thing left is the self — cogito ergo sum — of which we can be certain. We can’t doubt the existence of our consciousness, as far as Descartes is concerned. Therefore the “real-est” form of reality is the mind.

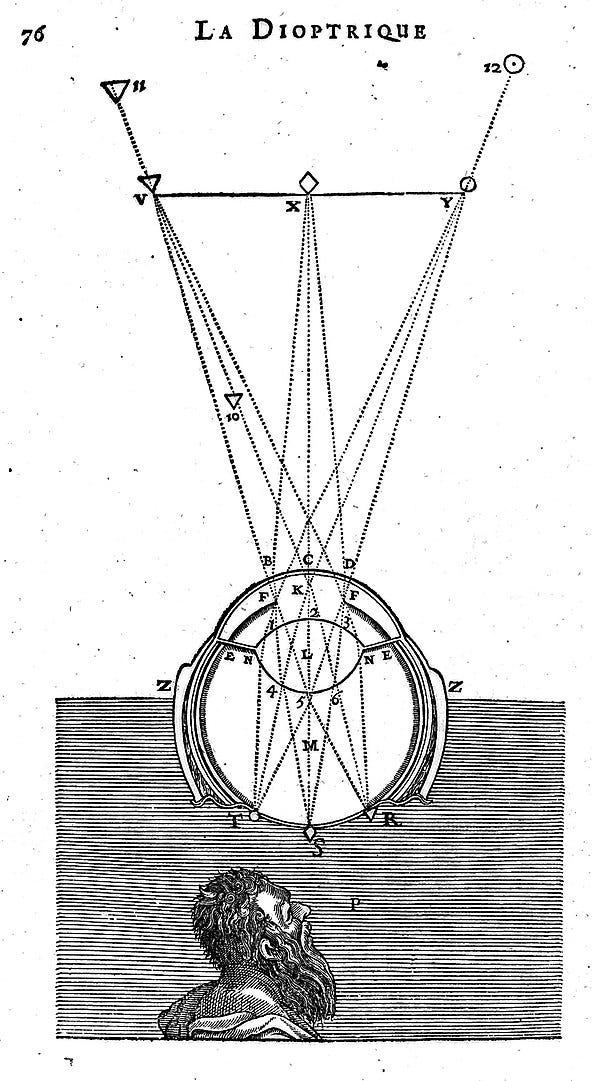

The material world is much more uncertain. We can’t know it in the same way we know our minds. Therefore we have to exercise reason, which Descartes sees as a critical procedure that starts inward with the self and extends outward to the world. In other words, Descartes is describing a radical division between the subjective and the objective, mind and matter, or what he calls res cogitans and res extensa. The fancy and confusing shorthand for all this is known as “Cartesian dualism.”

Charles Taylor captures some of the implications of Descartes’ argument in Sources of The Self:

We have to objectify the world, including our own bodies, and that means to come to see them mechanistically and functionally, in the same way that an uninvolved external observer would.

By positing a disengagement, or detachment, from the material world, Descartes turns the world into an object that we observe, study, test, and ultimately manipulate. If we once acted in the world, with the correct exercise of reason, we now have the power to act on the world — hence the common way of describing Descartes’ worldview as “mechanistic.” A helpful description, I think. If the world is mechanistic, we just need to learn how it operates; if physical reality is mere machine, then with the right instruction manual, we can use it as means to achieve our ends.

Perhaps you can see where this is headed. Descartes offer a glimpse in Discourse on Method:

... After I had acquired some general notions concerning physics ... I thought that I could not keep them hidden without sinning greatly against the law which obliges us to promote as much as we can the general good of all men. For my notions had made me see that it is possible to reach understandings which are extremely useful for life, and that instead of the speculative philosophy which is taught in the schools, we can find a practical philosophy by which, through understanding the force and actions of fire, air, stars, heavens, and all the other bodies which surround us as distinctly as we understand the various crafts of our artisans, we could use them in the same way for all applications for which they are appropriate and thus make ourselves, as it were, the masters and possessors of nature.

With the benefit of hindsight, Descartes’ enthusiasm appears naive and arrogant, even foreboding (masters and possessors of nature?). But the tone and tenor are typical of the era: the Enlightenment wasn’t just pale men in wigs and waistcoats. (Though it was a little, obviously. Auden has a great zinger in “A Walk After Dark” in which he describes the “clockwork spectacle” of the stars as “Impressive in a slightly boring / Eighteenth-century way.” Point, Auden.)

Still we’re talking about a period of passionate interest in the occult. Alchemy was a serious intellectual pursuit. Witch hunts were all the rage, reaching a peak during Descartes’ lifetime. As many people have noted, irony is one of the most powerful forces in history, and the Enlightenment is a case in point.

Let’s not overdo it, though. While few today would identify as Cartesians, practically no one would deny his influence. Without Descartes, maybe there is no Newton. Without Descartes, maybe there is no modern medicine. A certain school of thought likes to blame Descartes for anything bad that may have happened in the past four hundred years, but that seems like to put a lot on anyone.

At the same time, our relationship with the world is changed after Descartes. (Acknowledging that our is doing a lot of work throughout this email.) Previously our relationship was personal, participatory, and, in some sense, two-way. But for Descartes, the quest for certainty precludes any personal relationship. If there is a chasm between my subjective knowledge of reality and reality as it actually is — objective reality — the only way to know anything is impersonally, at a remove.

I am paraphrasing in the extreme, and not so much scratching the surface as dusting it with a light, feathery brush. But I think what Newbigin is arguing, and I think what you are too, is that certainty can only be maintained in a vacuum. Borrowing your language, certainty can only be claimed by people (nerds) who, in order to prove what they consider to be obvious (self-evident) truths, confabulate (manifest) another world (metaverse) in order to accommodate those truths.

And for a little while the scheme seems to work. After all, certainty is sexy. But ultimately the scheme collapses, as it must. If the disciple of certainty chooses to bury his head in the sand, so be it. He can’t, however, bury his head in the sand and call it a groundbreaking.

On a final note, the story of how Descartes discovered his philosophy may be revealing. In the winter of 1619, he was billeted in Ulm, Germany, a young solider and recent law school graduate contemplating what he should do with his life, as restless twenty-three-year-olds do on blistery nights in strange countries, far away from home. To escape the cold, he’d booked a room featuring a porcelain stove, the latest and greatest in interior heating. He must’ve felt relieved. Finally somewhere to rest and think. A clean, well-lighted place, as Hemingway put it.

What happened next is disputed. The legend is that Descartes actually curled up inside the stove, shaman-like, ruminating on the nature of reality — though it seems more likely that he simply propped up near the stove and inhaled a few heady fumes. In any event, he had a series of dreams over the course of his three-day stay that inspired him to radically rethink the traditional understanding of the self, the world, and how we know what we know. The seeds of I think, therefore I am had taken root.

But why has the story of the stove had such staying power? I think in part because it resonates with the popular image, or caricature, of the solitary thinker, as prevalent in Eastern cultures as it in Western. But perhaps the real reason is that the stove is such a compelling metaphor, comparable to Plato’s cave, as argued by Peter Hankins. As a self-enclosed machine — in other words, as a kind of vacuum —the stove perfectly represents Descartes’ inward-oriented philosophy, designed to produce indubitable, self-evident truths.

Only a decade or so prior, just across the English Channel on the stage of the Globe Theater, Hamlet contemplated a similar philosophical puzzle, and even used a similar image. But where Descartes found certainty, Hamlet is left, as ever, in doubt: “O God, I could be bounded in a nut shell and count myself a king of infinite space” — before the rub — “were it not that I have bad dreams.”

So we’re back to square one. Is absolute certainty possible? How do we know the truth? Can we know the truth? More later.

Jordan