Editor’s Note: Stan Musil and his roommate, Downstairs Eddie, are back with a few more non-Christmas music recs. I realize it is now Passover, Easter, Ramadan, etc., but I doubt any of the following are holiday songs, strictly speaking.

As a programming note, for now I’ve decided to link any music via YouTube rather than directly to a specific streaming platform. This seems like the simplest solution (read: it’s the method I’ve seen elsewhere), but let me know if you’ve got a better idea. Because videos won’t play directly in the email, it might be easier to open this in your browser, which I think looks better anyway. You can also read it in the Substack app on your phone, though I can’t in good conscience recommend spending more time on your phone.

As always, you can reach me at happyfew@substack.com.

By Stan Musil

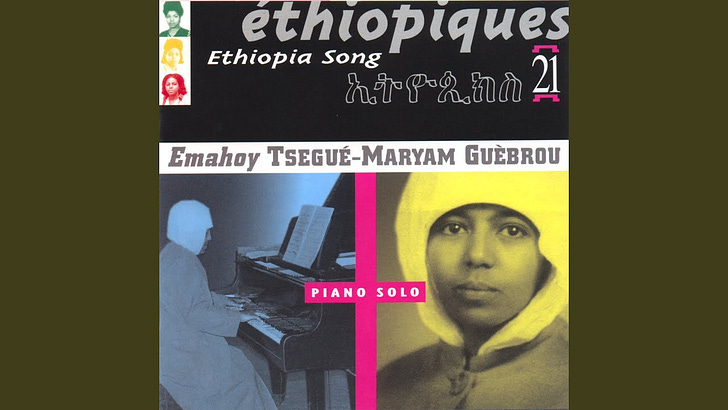

Emahoy Tsegué-Maryam Guèbrou

Rest in peace to the Ethiopian nun and pianist, who has died at age 99. I learned about Guèbrou in an excellent piece by Ted Gioia a few years ago. There’s not much else to say other than to implore you to listen. Listen!

Big Thief, Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You

Big Thief performs small miracles. Or, Big Thief proves miracles resist modifiers: a miracle is a miracle. Or, I’m new to the band and liable to the zealotry of the converted.

Either way, my introduction to Big Thief was “Pretty Things,” the opening track from Capacity. That song alone justifies the miracle thesis.

Then there’s the newest album. Pitchfork gave it a 9.0 rating and compared it to Tusk, The White Album, and Wowee Zowee, before declaring it “a sprawling statement with little concern for outward cohesion” — fair — “offering some combination of kaleidoscopic invention, striking beauty, and wigged-out humor at any given moment” — fair — “but not a particularly clear path from one song to the next” — fair. All fair, but helpful? To my mind, this is a little like the dinner party host who brings out a very rare bottle of wine, explains to his guests just how rare (i.e., expensive) that bottle is, then loudly disclaims before anyone can take a swig, “it’s not for everyone!”

So allow me to be clear: Dragon New Warm Mountain I Believe In You rules. And as the band’s loosest, most fun album, it feels like it’s for everyone.

Big Thief are still bonafide masters of traditional and indie folk. See “Sparrow,” a personal favorite. But where they’ve really excelled is in the stuff that’s harder to define: “Time Escaping,” driven by an array of pot-and-pan-ish percussion, and “Little Things,” a song which wouldn’t be out of place on a Bon Iver album, featuring a fuzzy, distorted guitar that drones, warbles, and burps.

Or, consider “Spud Infinity.”

This song is goofy as hell. But buried in the goofiness, miraculously, are seeds of real profundity. I love it. Yes, there’s the jaw harp — that thing making the old-timey boing boing sound. But there’s more here. As a person who often doesn’t care much about lyrics, or otherwise mishears them, Adrianne Lenker’s lyrics continue to demand my attention, whimsical and full of wordplay.

When I say celestial

I mean extra-terrestrial

I mean accepting the alien you’ve rejected in your own heart

When I say heart I mean finish

The last one there is a potato knish

Baking too long in the sun of spud infinity

To my ear, that sounds like Allen Ginsburg if Allen Ginsburg had a sense of humor. In which case, it sounds like something penned by Charlie Mackenzie in So I Married an Axe Murderer.

When I saw Big Thief live last month with Downstairs Eddie (formerly a holdout, now a fellow convert), they performed “Spud Infinity” with the exact degree of silliness and glee I’d hoped they would, bopping and pecking about the stage, feigning a kind of chicken dance that reminded me of The Soggy Bottom Boys.

It’s a 10.0, for me.

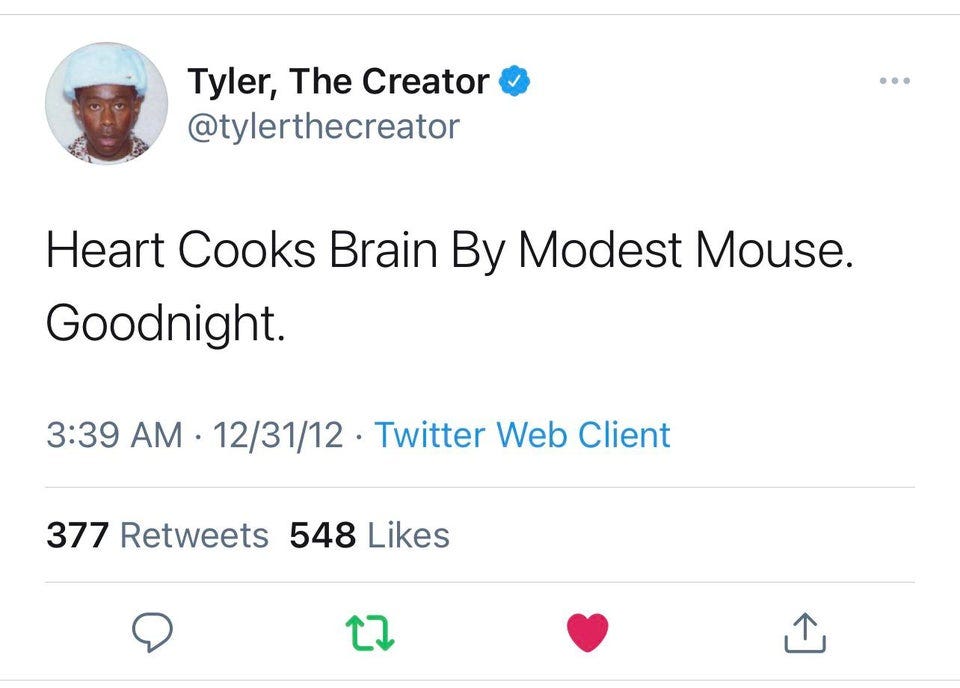

Modest Mouse, The Lonesome Crowded West

If this album is your thing, it’s probably really your thing. It’s really Downstairs Eddie’s thing.

In addition to “Heart Cooks Brain,” I’d call out “Teeth Like God’s Shoeshine” if for no other reason than —

The malls are the soon-to-be ghost towns

— a line delivered in 1997. Modest Mouse as commercial real-estate wonks: I wonder what they make of the pivot to adaptive reuse projects? Also, I can’t really condone the use of crystal meth, but if that’s what “Styrofoam Boots/It’s All On Ice, Alright” is about, I guess I get the appeal.

The only song that feels out of place on Lonesome Crowded West is “Trailer Trash.” That’s not to say it’s a bad song — as of this writing, it’s the album’s second-most streamed on Spotify — but it’s very much a pop song, and in a middling jam band kind of way. More importantly, “Trailer Trash” is the only song on the album that you could realistically make out during. In particular, I’m thinking of the final section, starting around the three-and-a-half minute mark. For lack of a more refined vernacular, let’s call it the make out melody. (Note that I’m not at all talking about the more familiar concept of a “make out song,” mostly because I doubt anyone makes out for the duration of an entire song. I don’t know.)

What constitutes the make out melody? There are no hard and fast rules, but “Trailer Trash” capitalizes on at least three important criteria.

First, placement. We pull into make-out territory almost exactly two-thirds of the way into the song. A good make out melody knows how to flirt: like a canny medieval lover, it will delay and delay and delay, testing and teasing its audience until consummation can no longer be put off.

Next, a simple chord progression and regular rhythm. “Trailer Trash” repeats the same three chords over and over. No one is out here swapping plaque to King Crimson, or Trout Mask Replica, or, God forbid, Primus.

Finally a good make out melody has a come-down, some sort of signal to let you know it’s closing time (i.e., wrap it up or hurry up). In the case of “Trailer Trash,” the cymbals crash, the drums land hard, and the guitar lingers ostentatiously. I recently learned of what are called terminal climaxes, “which appear frequently in rock songs after 1990, [and] are characterized by their balance between the expected memorable highpoint (the chorus) and the thematically independent terminal climax, the song’s actual high point, which appears only once at the end of the song.”1 I don’t know if the final third of “Trailer Trash” technically qualifies, but the phrase’s suggestive eroticism seems appropriate.

Your greatest exposure to the make out melody, of course, is as a teenager, when you still occupy a world in which people actually make out. But here’s the catch. The make out melody has the power of revelation — and the way in which it wields that power is decisive and terrible. Just think. How many make out melodies have revealed, or reaffirmed, a friend zone? How many make out melodies have suddenly, rudely identified a third wheel? Or worse, a fourth, fifth, sixth wheel? Picture it. Some unsuspecting nub with a freshly-minted learner’s permit standing in the general admission section of a concert. He may be hapless, but he’s not an idiot: given the venue’s curfew, the band is playing what must be the last song. The make out melody drops, and our hero knows his fate. Full completion — terminal climax — can only be achieved in the moment of exclusion, when everyone around him turns to their neighbor and wordlessly, breathlessly, starts using their tongue like an industrial-grade plunger.

I wish there was a word to describe this singular sensation. Maybe there is in German. The queer, queasy feeling that occurs when you are at once grossed out, jealous, and lonely.

So it goes with the make out melody, the very ground and being of teenage melodrama.

Billy Joel, “Scenes From An Italian Restaurant,” Live at Yankee Stadium

From my understanding, and to make a very broad generalization, there are basically two schools of history, which can be traced back to Herodotus and Thucydides. The latter practiced history as a science, presenting and analyzing facts, figures, and other documentary evidence to provide a cause-and-effect explanation of past events (specifically, past wars). The former, the older, practiced history as an art, recording the facts, arranging the facts, and occasionally accentuating the facts. After all, some facts resist explanation.

The above recording follows the school of Herodotus. It tells us absolutely nothing about why June 1990 was the way it was — it doesn’t need to. It simply is June 1990. And friends, June 1990 is something else.

The definition I’ve quoted appears in the abstract of the linked paper by Brad Osborn. Credit to Cole Cuchna for introducing me to the concept in a Bandsplain episode on Radiohead. Specifically, he was referring the conclusion of “Karma Police,” though once you know what a terminal climax is, you’ll realize Radiohead uses terminal climaxes all the time. Credit to Radiohead. Another example would be the end of “Hey Jude.” Credit to The Beatles.